By: Noah D.

If you spend any time in marinas, ports, and coastal towns in the British Isles, there’s an acronym that seems to be everywhere. Literally. Go in any gas station, cafe, pub, ferry terminal, etc, and you’ll see something about the RNLI somewhere.

For my American readership – or those who are only familiar with the militarized USCG – it might come as a surprise that the RNLI is actually run as a not-for-profit charity. It is an NGO. Even more astounding to me is the fact that most of these guys are un-paid, but highly skilled, volunteers. Seeing them in action first-hand and then finding out that they’re doing it basically for free is truly amazing.

The Conditions

We headed out of Falmouth early on Monday morning. Just before 6am, actually. In England this time of year, that means two hours before dawn. Our weather window was a solid 48 hours and we were projected to arrive in Cork around 5pm the following day if we maintained a moderate speed. But the Atlantic fronts that were coming in were not expected to be overly strong, just a jump from 15kts to maybe 25kts of wind: certainly nothing that a reef in the main wouldn’t take care of. Well… as we rounded Lands End just before dark (4:30pm) and headed northwest toward Cork, Ireland, the wind shifted… to the northwest. This meant beating a due north course for a while in the deep darkness of the Bristol Channel.

This wasn’t that bad, either. The tides were with us and we were clocking an easy 6+kts in 15kts of air with precautionary reefs in the main and jib. I don’t think we saw 20kts flash on the anemometer the whole night and the seas were slight although with a normal North Atlantic swell. Add this with the VHF forecasts from the MET Office every three hours forecasting Force 4 to 5 that would be shifting from north-northwest toward the west and to the west-southwest… this was backed up by PassageWeather (checked via phone before we lost 3G service off Lands End). So, everything was looking good for our landfall.

Well… the winds only shifted around dawn and by that point we were quite far off our rhumb line. But they did shift! And we made straight for our destination on an easy, fast, port tack. There were a few moments we were hauling along over 7kts over the ground. We felt good! Tired, but good!

Around this time, we were out of range of the VHF aerials. We could hear the high-power HM Coast Guard announcements for the weather, but when we switched to the proper channel, the actual broadcast was too weak to make any sense. No matter… the forecasts all had been fine.

By the time we were in range of the Irish CG weather broadcasts, there was a Wind Warning and Small-craft Advisory in effect. This meant that there had been a new update superseding the previous mild conditions and moving up the bad weather almost a full six hours. Dark fell and we were at two reefs still pounding upwind and against the waves (but still making well over 5kts). We were less than 50 miles offshore and we decided to turn downwind and make for the closest coast. With the main down and flying a tiny scrap of headsail, we blew down wind and kept up with the building waves. We headed as close as we dared to quarter the following seas and the wind coming out of the west.

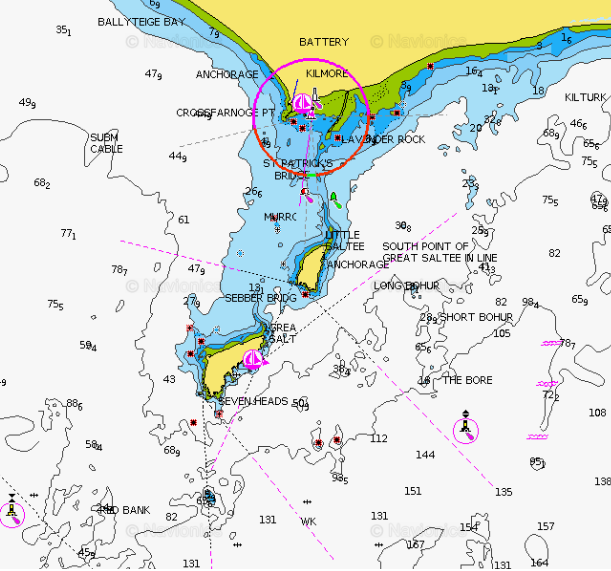

I was manually steering of course because no autopilot can handle stuff like that. So Lynn was reading aloud from the Reeds Almanac for a place to go. Around 20 miles offshore – also past 2200 hours – we attempted calling a marina before it got too late to see if we could reach a harbourmaster. When we called Kilmore Quay, the harbourmaster did not answer, but fishing vessel Mary Catherine broke in: “Nobody is there this time of night, but if you’ll go to Channel 12, I might could help you.”

I was manually steering of course because no autopilot can handle stuff like that. So Lynn was reading aloud from the Reeds Almanac for a place to go. Around 20 miles offshore – also past 2200 hours – we attempted calling a marina before it got too late to see if we could reach a harbourmaster. When we called Kilmore Quay, the harbourmaster did not answer, but fishing vessel Mary Catherine broke in: “Nobody is there this time of night, but if you’ll go to Channel 12, I might could help you.”

Again, I’m steering, and Lynn talked to F/V Mary Catherine on the VHF for a little while to find out information about the area and see what we could do about shelter. One of his suggestions was to call the Kilmore Quay lifeboat station and see what they recommend. Until now, I had only thought that the lifeboat was literally that: a boat to save lives. And, we certainly were not entering “life threatening” status yet. But, with an uncertain (but low-er) amount of fuel and still almost 3 hours off the coast, motoring upwind, into the current, and against the waves was a dubious prospect. We still bombed along at more than 7kts with barely any sail up.

It was about this time that I calculated that we were probably going to miss the southeastern tip of Ireland. Which would have put us many many more hours at sea before landing somewhere in Wales. If we passed around Tuskar Rock, there might be a chance of the seas calming down enough for us to motor upwind into Rosslare or Wexford, but still… it was a chance.

So, call the lifeboat station, we did. Of course, the Rosslare Coast Guard talked to us for a little while, and dispatched the lifeboat to see what assistance they could provide. By that point, the seas were ridiculous and the wind gusts were flashing 40kts… 42kts… Finally, instead of trying to transfer any fuel over to us, the decision was made to simply tow us the rest of the way in to Kilmore Quay. And, out they came. Like something from a movie, this massive powerboat, lit with millions of candlepower spotlights, came barreling out of the 4-5 meter seas as a tank might growl over rolling hills. They threw over a tow rope as big around as your forearm and drug all 24,000lbs of Proteus through Force 8-9 winds and huge waves the two hours to safety. In fact, it was like we weren’t even there: they pulled us at over 6kts for two hours as we held on for quite a wild ride. Not one I would ever want to take again, mind you.

Now, sitting here at Kilmore Quay, we are fine. Proteus is fine (although a little shaken up, literally and figuratively). Some people say: “Respect the sea.” And, prior to this, I would have said: “Yes, I do respect the sea!” But that’s akin to reading all about travel and foreign lands without ever having set foot on a plane.

Now, sitting here at Kilmore Quay, we are fine. Proteus is fine (although a little shaken up, literally and figuratively). Some people say: “Respect the sea.” And, prior to this, I would have said: “Yes, I do respect the sea!” But that’s akin to reading all about travel and foreign lands without ever having set foot on a plane.

I tell you now: we sailors of Proteus, we respect the sea. I’ve lived near and on water my entire life, but no movies or books or photographs can tell you what it is really about out there. And, secondly, we respect the first-responders – the men of RNLI lifeboat 16-18 – that came out to make sure we made it into their harbour safely.

The Aftermath

So, you may wonder, how “at risk” were we really…

To be completely honest, any offshore passage like this is a risk. However, a powerful and well-equipped sailing vessel like Proteus cuts down those risks significantly. And – not meaning to sound at all prideful – but we took precautions a long time ago in our sailing studies and research that assisted us in heavy-weather sailing like what we experienced on the Celtic Sea: there is no substitute for knowing what to do in particular situations.

But, most importantly, we had the assistance of F/V Mary Catherine at first, then the Rosslare CG, and finally the guys at RNLI Kilmore Quay to come fill in the gaps to make sure that we never were classified as a “vessel in distress.”

But, most importantly, we had the assistance of F/V Mary Catherine at first, then the Rosslare CG, and finally the guys at RNLI Kilmore Quay to come fill in the gaps to make sure that we never were classified as a “vessel in distress.”

Proteus never took on water (except into the cockpit) and never suffered a knockdown, but the situations were such that the RNLI weren’t just making a milk run. Talking to the guys later at 3am tea, one of the lifeboat crew told me: “We’ve all been there.” Perhaps he was just being gracious, but if I’m taking steps to someday be as capable and as good of a seaman as the crew of the 16-18 by going through a Fastnet gale, I’m almost glad it all happened the way it did.

But… if it is up to me? Never again.

Could we have done anything differently? I’m actually not sure. Talking to a few people and analyzing the situation, it was a case of a winter North Atlantic frontal system doing its normal thing and saying: “Haha! You think you can predict me!? Gotcha!!” Had we kept significant spare fuel on board, I might have felt better about powerboating upwind and upwaves into such conditions. If we continued to live in the high-latitudes – which we have no intention of doing – we could have done well with a storm trysail and a storm jib. I feel fairly confident that the added stability of forward motion would have contributed to our comfort on board. Another option would have been to heave-to and wait it out. But by that point, the main was down and putting up a double-reefed main in those conditions would have been foolhardy.

A New Chapter Begins

We are young at this. I’ve been sailing more than a decade and this was my first true test of serious gale conditions. Even after 700 miles of sucky English winter weather, this ratcheted up the playing field considerably. However, the inexperienced become experienced through experience: not by reading books or by sitting at the quayside. Next time, it might be 800 miles offshore instead of a mere 12. The things we learned in this gale will keep us safe and make the difference when no lifeboats are on hand.

Our original destination was Cork, Ireland, to keep the boat over Christmas and the “worst of the winter weather” as we prepare for our Big Trip this spring. As luck would have it, I suppose, we could not have landed in a better place. Kilmore Quay has a relatively small marina, but it is a true, old-school, maritime village. It has everything that we need. So, this will be our base until we head south in the spring.

Lynn and I look forward to seeing flowers bloom and heading back toward the sun again. For that, stay tuned…